Tony’s Short Stories: The Dauntless

Welcome to a journey back in time to the Pacific Theater of World War II, where the fate of nations was shaped in the skies. In today’s episode of Tony’s Short Stories, we’re exploring a saga of resilience and legacy—the Douglas Dauntless, a dive bomber that defied obsolescence and became one of the most effective aerial weapons in history. Known affectionately by its pilots as “The Clunk,” this aircraft proved its worth in some of the most critical battles, from the Coral Sea to Midway, helping to turn the tide of war. Stay with me as I dive into the legacy of this underestimated war machine and uncover how it earned a place in history as one of the Navy’s most revered planes.

“The Dauntless”, by Gaither Littrell, Western Editor of Flying, published in the January 1945 issue of Flying magazine.

Obsolescent when war began, the Dauntless carried, with honor, the brunt of the early Pacific battles.

“Only development of planes with greater speed and range induced the Navy to cease production of what probably was the most destructive single air weapon in its arsenal. (Signed) James Forrestal, Secretary of the Navy.”

This high tribute from the Secretary of the Navy has just been given, an airplane that generally is credited by Naval aviation with paving the way for winning the Pacific war.

Yet this “most destructive single air weapon” was obsolescent when it was making these great victories possible!

Affectionately known to pilots as “The Clunk,” this outdated plane, whose production has just been 5,936 built, is completed with the Douglas SBD dive bomber-the Douglas Dauntless.

As long as men discuss the great battles of the Pacific, the story of the Dauntless will be told. It will go something like this:

From December 7, 1941, to the summer of 1944, Dauntlesses had flown more than 1,190,000 operational hours. Twenty-five per cent of all operational hours flown off aircraft carriers were by the Dauntless. This also includes the time accumulated by other type planes operating from small carriers that do not carry Dauntlesses. The plane has run up 26 per cent of all Marine Corps operational flying hours.

In a recount of their part in the war, the Dauntlesses will be remembered most vividly for their work in the great holding battles from the Coral Sea engagement, May, 1942, up to the last big Japanese strike against Guadalcanal in November, 1942.

In that seven-month period, Dauntlesses are officially credited as follows:

Sinking of 14 enemy aircraft carriers, 14 enemy cruisers, six enemy destroyers, 15 transports and cargo ships, and scores of smaller craft. Additionally, in co-operation with Grumman Avengers, surface gunfire and submarines, they destroyed two more carriers, one patrol ship, damaged three other carriers, five patrol ships, 11 cruisers and five transport and cargo ships.

Throughout all their missions-from the attack on Pearl Harbor to the recent retaking of Guam-the Dauntlesses are revealed by the Navy to have maintained a lower ratio of losses per mission than any other carrier-based plane.

Dauntlesses mixed it up with Zeros the first day that Japan became an armed enemy of the United States. One Dauntless operating from the U.S.S. Enterprise, which was in the proximity of Hawaii at the time, is credited with destroying the first enemy plane of the war.

With the Grumman Wildcats and Douglas Devastator torpedo planes, the Dauntlesses were given the task of delaying the onrushing Japanese drive until our aerial military might could be revived with new, better planes.

First offensive venture of the Dauntlesses came only three months after Pearl Harbor, when Admiral William F. (“Bull”) Halsey, Jr., took a small task force into the Marshall and Gilbert Islands in February, 1942.

From the decks of the “Big E,” squadrons of Dauntlesses climbed to rendezvous, approached their targets and peeled off one by one, hitting Japanese ships, hangars, airstrips and troop bivouacs with 1,000-pound bombs.

The same force hit Marcus and Wake Islands in March, 1942. Admiral Halsey received a Presidential citation for that brave, boldly-executed operation. With the entire ship’s crew mustered top-side, the Admiral was presented with the decoration.

About this time all was not going well at Naval air stations on the mainland. The Navy needed dive bomber pilots but not enough Dauntlesses could be spared from combat.

At San Diego, pilots assigned to the fleet were in their last stages of advanced training. They needed to familiarize themselves with the Dauntlesses but none were available. Then one morning the air station field was dotted with 18 battleworn SBD’s flown in during the night. And for two weeks the new pilots had a chance to gain a few minutes flying time in these planes until a carrier heading for the Pacific battle area stopped by San Diego, picked up the 18 planes and headed to sea.

Production of the Dauntless had begun again at the Douglas El Segundo plant, however, and, in late March, 1942, the first new batch of Dauntlesses were coming off the line. Training caught up to schedule soon thereafter and new squadrons were sent to the war zones.

In May came the Coral Sea battle, where the Dauntlesses sank one Japanese carrier, badly damaged several others and scored hits and near misses on other shipping. Tulagi Harbor was the next surprise action of Dauntlesses, flown from the U.S.S. Yorktown. Dive bomber pilots and their gunners here taught the Japanese that Dauntlesses were also tough babies in a dog-fight. Their guns shot down several Zeros in this engagement.

Then came the Battle of Midway. It was a triumph for the Dauntless. In that historic engagement of June, 1942, Dauntless planes operating off the Enterprise, the Hornet and the Yorktown dive-bombed and sank at least four enemy carriers and damaged many other warships of the Japanese fleet. Never before had one type of aircraft done so much damage to capital warships.

Dauntlesses which had fought their way through the violent fighter and antiaircraft opposition were returned to Pearl Harbor after the battle. Here the pilots and ground crews became aware of the sturdiness of the Dauntless. Many had gaping wounds in their wings, fuselages and tail surfaces. It seemed incredible that an airplane could absorb such punishment and still manage to return to the carrier for a landing.

In the summer of 1942 the carrier fleet moved into the South Pacific. There the Dauntlesses carried on the tedious work of flying long search patrols ahead of the fleet and hovering in protection over the task forces hour after hour. The Dauntless bore the flying burden.

In the fall of 1942, the U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal, with Dauntlesses spearheading the attack. When Henderson Field was secured, Dauntlesses landed and began operations as shore-based bombers and patrol planes. Marine Corps pilots put them to work in as trying a test as any aircraft has undergone.

With only a few Dauntlesses, the Marine flyers covered the long stretches northwest of Guadalcanal, flying night and day to spot the “Tokyo Express,” the enemy’s fast-moving cruiser and destroyer forces which attempted to carry replacements almost daily from Bougainville to Guadalcanal.

Usual procedure followed by Dauntless Marine pilots was to take off in the afternoon from Henderson Field and attack the “Tokyo Express” in clear daylight. At night they would attack docks where the ships that had withstood the afternoon bombings were unloading troops. And then in the mornings the Dauntlesses would fly out to attack the Japanese ships as they headed back to Bougainville.

This ‘round-the-clock operation permitted only the barest minimum of upkeep. The worst days for the Dauntlesses were over by the end of 1942, when more and more planes of different types were poured into the Pacific area. The Dauntless no longer had to carry the terrific load virtually alone.

The Dauntlesses still had an active part to take, though. When the drive started up the Solomons chain, these planes were given the hazardous job of pinpoint objective bombing, such as gun emplacements, barges, fortifications, radio communication centers and stubborn points of resistance. As the Marines continued to advance, so did the Dauntlesses, operating from one new landing field after the other.

When the carrier offensive was renewed in the summer of 1943, Dauntlesses were the old reliables once again. But this time they were strictly on the offensive in the Central Pacific. They took part in the first small-scale carrier strike at Marcus Island on September 1, right up on and through the attacks on Wake, the Gilberts, the Marshalls, Truk, Rabaul, Palau, Hollandia, Saipan and Guam.

And the Dauntless was considered obsolete! No one knows that better than E. H. Heinemann, Dauntless project engineer and currently chief engineer of the Douglas El Segundo (California) plant, where the last Dauntless was just completed. He says:

“The Dauntless was a pre-war combat plane and has been repeatedly considered obsolescent. As late as June, 1941, it was stated by high-ranking officers that it was dead and that there would be no further orders. While it is true that performance is not all that is desired, it still is the only unrestricted dive bomber in service in this country.”

The Dauntless was conceived back in 1934. At that time John K. Northrop, one of the leading aeronautical geniuses of the nation, headed the Northrop Aircraft Company, Inc. (this later became Douglas’ El Segundo division and is not to be confused with Northrop Aircraft, Inc., now in operation at Hawthorne, California). Northrop was personally in charge of the engineering department and shop. Associated with him was Ed Heinemann.

That year the company received an invitation from the Navy Department, Bureau of Aeronautics, to bid on a dive bomber. The company also was in the throes of developing a plane for the U.S. Army which later became known as the A-17A.

Northrop selected Heinemann as project engineer on the Navy job and Heinemann prepared the initial drawings and bid. Those were tense, exciting 18-hour working days for Northrop and Heinemann. The dive bomber bid was on a competitive basis, with Northrop arrayed against the engineering talents of Brewster, Vought, Curtiss and Great Lakes aviation companies.

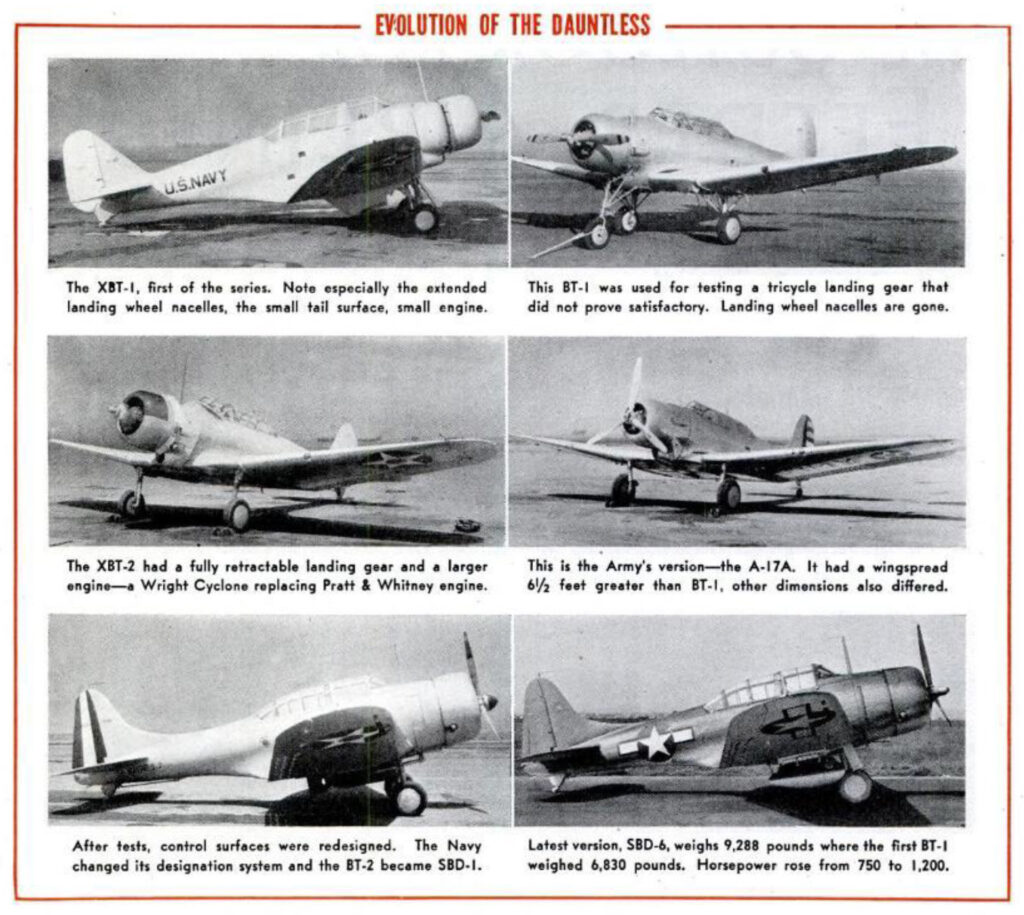

It was a gratifying triumph for these men when the Navy Department accepted their bid and awarded Northrop a contract for one experimental XBT-1 dive bomber. Engineering work and the experimental model were completed in 1934 and 1935. After six months of tests and incorporation the into the plane of Heinemann-designed perforated, or “Swiss cheese” type dive flaps, the first XBT-1 was delivered to the Navy at Anacostia in December, 1935.

Meanwhile the other companies were eliminated because the Brewster was late in completion and developed so many difficulties that only a few were built, although it was reported faster than other planes designed. The Great Lakes design was a biplane which was eliminated because it was of much less advanced design. The Vought had the best performance but was seriously handicapped in diving because it relied upon the propeller as a dive brake. This was a constant source of trouble and required that the plane be operated under serious restrictions. The Curtiss was also a bi-plane which had been under construction in earlier design for several years. It was purchased in moderate quantity but was discontinued because of obsolescence.

“The difficulties of designing a successful dive bomber can be understood,” explains Heinemann, “when it is considered that of the five original competition contenders only the Dauntless was sufficiently successful and rugged enough to endure this length of time. Furthermore, the famous Curtiss Helldiver, the result of a design competition held in the summer of 1939, has only recently come into service.”

After conducting its own tests on the XBT-1 for two months, the Navy accepted it as a satisfactory service type and a contract for 54 BT-1’s was awarded in 1936.

“I remember how our small company was striving for business at that time,” Northrop recalls, “and what a tremendous boost it gave all of us when the contract was awarded. Why, 50 airplanes then was comparable to an order for 500 today!”

Although it was not the same airplane, the BT-1 was similar in many respects to the A-17A and the engineering done in advance on the A-17A served as a guide in the construction of the BT-1. Both were of multi-cellular monocoque structure; had the same aerodynamic characteristics and airfoil sections; the same engines, and similar flaps, although the BT-1 incorporated improved flaps which served as dive brakes.

The A-17A’s had a wing spread of 48 feet, whereas the BT-1 had a span of 41½ feet, the wings purposely shortened for carrier operation. Other dimensions differed correspondingly.

During 1937, while the delivery of BT-1’s was being delayed by a company strike, engineering was begun to convert the BT-1 into a new model designated the XBT-2. This airplane had a fully retractable landing gear and a Wright Cyclone engine instead of the Pratt & Whitney engine installed in the BT-1’s. It was flown in April, 1938, and delivered to the Navy for trials. It is interesting to note that, in 1938, experiments with a BT-1 carrying a tricycle landing gear were conducted. The gear was abandoned as unsuitable shortly after.

Northrop assisted in the development of the XBT-2, but in the latter part of 1937, he sold his stock in the Northrop Company to Donald Douglas, who turned the plant into what is today, the El Segundo division of the Douglas Aircraft Company, where all Dauntlesses were produced. Northrop left Douglas on January 1, 1938.

A contract was obtained for a production quantity of BT-2 airplanes in February, 1939. With this order came a change in the Navy designation. The plane became the SBD-1, forerunner of the current SBD series. It meant “scout bomber, Douglas.”

As the result of operating experience and tests conducted with BT-1’s, new stability and control specifications were established, making it necessary to redesign all control surfaces of the Dauntless in 1939. Many airplanes under partial construction were affected. It was necessary under this new requirement for the company to run exhaustive fight test programs, during which 21 different sets of tail surfaces and 12 sets of lateral control surfaces were constructed and tested.

These tests resulted in the Dauntless becoming a criterion for stability and control for this type of craft, but it caused a considerable delay in production. Deliveries were not started until May, 1940.

Success of this model resulted in contracts being awarded for the SBD-2, SBD-3, SBD-4, SBD-5 and the SBD-6. Changes in the model numbers can be accounted for by such relatively minor changes as voltage of the electrical system, increased power in the power plant, additional fuel tanks, etc.

Meanwhile, the Army had become interested and had placed an order for several hundred A-24 attack bombers, which were SBD’s all over again with the exception of the landing hook needed by Dauntlesses for landings on aircraft carriers. These orders were filled at the Douglas plant in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The Dauntless today is a low-wing monoplane arrangement with aluminum alloy semi-monocoque construction. Its span is 41 ft. 6 3/8 in.; length is 33 ft. 1 1/4in.; and height is 15 ft. 7 in. Wing area is 325 sq. ft., loading is 29.3 lbs. per sq. ft. It has two-place tandem cockpits provided with sliding transparent enclosures. Self-sealing fuel tanks are carried in both center and outer wings.

Gross weight of the Dauntless is 9,288 pounds, whereas the BT-1’s were 6,830 pounds. Dauntlesses are equipped with a Wright R-1820-60 Cyclone engine, developing 1,200 horsepower, while the BT-1’s carried an R-1535 Pratt & Whitney engine developing 750 horsepower.

Top speed of the Dauntless is more than 230 m.p.h., compared with 219 m.p.h. of the BT-1. Terminal velocity of the Dauntless without dive brakes is over 400 m.p.h., while the use of dive brakes (one on the upper and one on the lower surface of the wing) reduces the velocity to under 300 m.p.h., thus improving dive-bombing accuracy and permitting closer approaches to moving targets. Rate of climb is over 1,400 ft. per min., cruising speed is 185 m.p.h. at 14,000 feet.

A bomb rack and displacing gear are provided under the fuselage for carrying and displacing either one 500-pound, or one 1,000-pound bomb in vertical dives; one rack also is provided on each outer wing for bombs in all sizes from 100 to 500 pounds, as well as depth charges and chemical tanks.

Two .50-caliber fixed machine guns are mounted in front of the pilot, one on each side of the instrument board and synchronized to fire between propeller blades. Two .30-caliber flexible machine guns are mounted in the rear cockpit, with both pilot and gunner protected by armor plate. The BT-1’s mounted only one flexible .50-caliber machine gun.

Handling characteristics of the Dauntless are outstanding. Because of their high maneuverability they have been used on occasion as fighters against attacking Japanese planes. Stability and control is maintained down to within five m.p.h. of the stalling speed, which is 78 m.p.h. There are few combat planes in which this rare condition exists.

The Dauntless series is the first upon which perforated dive flaps were used. The purpose of the holes in the flaps is to break up the eddys that flow off the trailing edge of flaps in order not to cause excessive tail buffeting. Fixed leading edge wing slots are provided to obtain aileron control after a wing stall.

Range of the Dauntless fully loaded is over 1,000 miles, while the service ceiling is 25,200 feet. Wing loading is 29.3 pounds.

To show how cost declines in aircraft building with volume production, it is revealed that it cost more than $85,000 to produce the XBT-1, while the 5,936th—and final—Dauntless to come off the line cost approximately $29,000.

Now that the Dauntlesses have more than fulfilled their purpose and are being replaced aboard carriers by newer and better aircraft, Heinemann and other Douglas engineers are engaged in designing more advanced craft for the Navy. They thought a short time back they had the answer in what was designated the BTD—bomber torpedo Douglas—but the Navy contract on the gull-wing, bomber—torpedo plane was cancelled after a few were constructed because too much time would elapse before they could be taken into combat in sufficient numbers.

There is one thing that is almost a certainty, though. And that is that no other plane in our aerial arsenal will store up so many surprises for the enemy as did the Dauntless.

As the last of the Dauntlesses rolled off the production line, few could have predicted the lasting impact this aircraft would have on the course of history. Obsolete when war began, the Dauntless defied expectations, becoming the unsung hero of the Pacific. From its nail-biting dives to its dogfights against enemy Zeros, the Dauntless not only survived but thrived in the most intense combat environments. I hope today’s episode gave you a glimpse into why this aircraft is remembered with such reverence. Thank you for joining me on this flight into history—tune in next time as I uncover more fascinating stories of aviation’s past.

Thanks again, and I’ll see you in the next one!

Discover more from Buffalo Air-Park

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.